In the current age of information, any technology you own could potentially be used as an avenue for attack, including your mobile phone.

In writing and publishing this piece, I am hoping to highlight the risk of linking a single invariable phone number across all of your online accounts, and how doing so could easily allow for an adversary to derive your personal phone number, and then use it to carry out attacks which require knowledge of the same.

The potential threat posed by someone knowing your phone number might seem trivial at most, until existence of vulnerabilities such as one that had recently affected T-Mobile are taken into account.

In the case of the previously mentioned vulnerability, an attacker could have used it to query sensitive, personally identifiable information of any T-Mobile subscriber by knowing just their phone number.

The data which was being leaked included information such as—account number, status and creation date, SIM IMSI number, e-mail address, encrypted security question answers, as well as details about when the account password was last changed.

Furthermore, the accumulated information could then be used to aid what is called a ‘SIM swap’ attack, which allows attackers to gain access to and have complete control over a person’s mobile phone number, including all incoming and outgoing communication (calls, text messages and voicemail).

Reconnaissance

This post was written with regard to the fictional target being from the United States, but based on context, it could very easily be adapted to work with persons from another country.

The attacker would need to determine the location of the target from their online presence.

This part is extremely easy, as most people reveal their current city on their Facebook page. However, if this information is not listed on their social media profiles, it would have to be gathered from other publicly available sources. The attacker would also require knowledge of the target’s e-mail address.

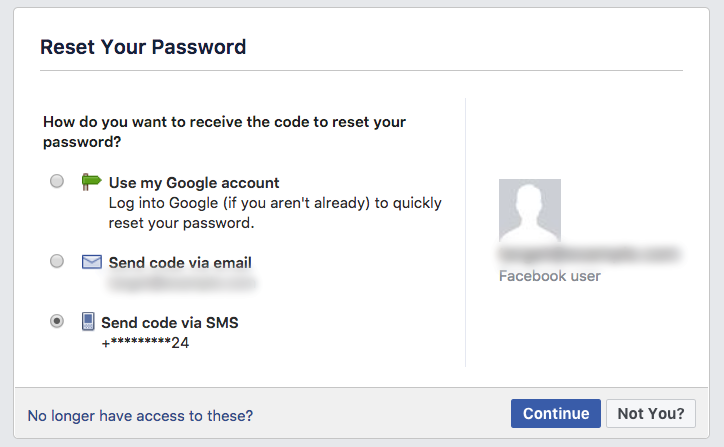

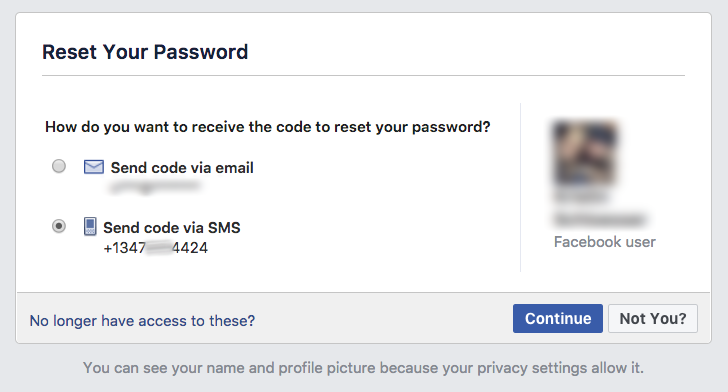

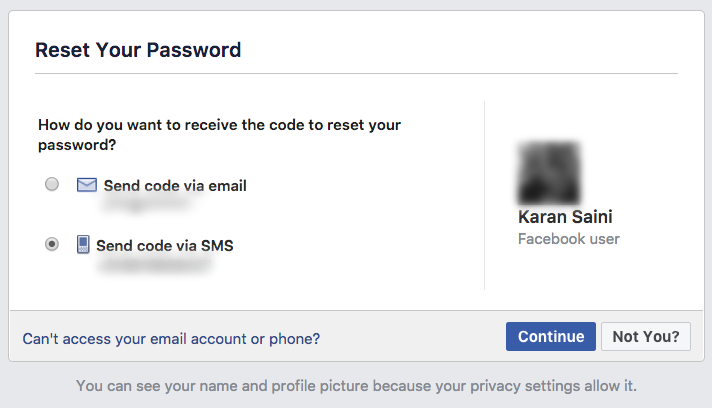

Once the prerequisites have been met, the attacker would head over to the ‘Forgot password’ page on Facebook or Twitter, and submit the email address or username of the target.

If the submitted e-mail address or username corresponds to an existing account, the attacker would be presented with the last two digits of the phone number linked to it.

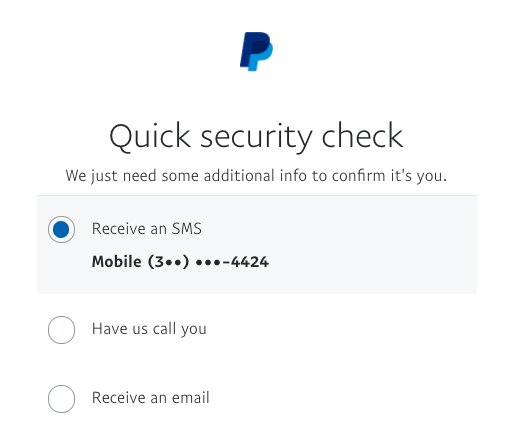

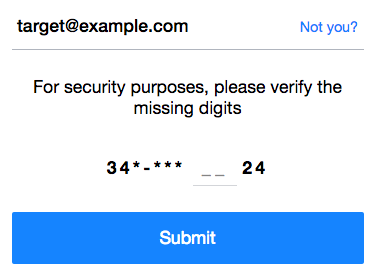

The attacker would then head over to PayPal’s website for more information regarding the phone number.

The process here is similar—the attacker would enter the e-mail address of the target on the ‘Having trouble logging in?’ page and use the response to add to the currently incomplete phone number.

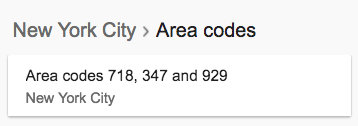

A look at the target’s social media profiles allows for a conclusion to be made about their current city of residence, which in this case is: New York, USA.

The attacker then looks through the assigned area codes for the city and finds that only one area code starts with the digit ‘3’—which, if you remember, matches the first one digit earlier retrieved from PayPal.

This information allows the attacker to confirm the first three digits of the phone number.

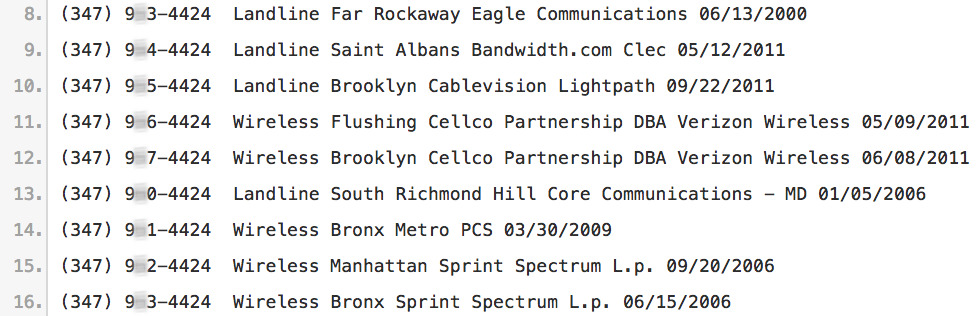

The attacker would now have to parse a list of all possible phone number prefixes (which would be the three digits following the area code) and adjoin them with the partially obfuscated phone number currently known.

Lastly, the attacker would have to manually submit and check off phone numbers from the compiled list, until either the full name of the target has been returned, or distinctive characteristics which are most likely to match the originally provided e-mail address have been identified.

It is possible to automate this part of the process, but it usually would not be needed as the list of possible phone numbers shouldn’t be too long to begin with.

Success! The previously obfuscated phone number is now fully known.

It is also possible to further verify whether the retrieved phone number belongs to the target (or not), by using various open source intelligence techniques.

For instance, unless you have explicitly disabled a certain privacy setting on Facebook, your full name and profile picture are displayed to anyone who submits your e-mail address or phone number on the ‘Forgot password’ page.

Another technique is to use Google’s ‘Forgot email?’ page, which allows you to submit a name and phone number to see if there is a corresponding Google account linked with the same.

Conclusion

The attacker would initially use Twitter or Facebook to gather information about the target’s location and to retrieve the last two digits of the target’s phone number.

PayPal would then be used to retrieve the first one and last four digits of the phone number. The last four digits retrieved from PayPal would help conclusively verify whether the last two digits retrieved from Facebook were accurate and up-to-date.

The target’s general location and previously retrieved first one digit would then be used to make an educated guess about the area code (first three digits) of the phone number in question.

The phone number prefixes (which are the three digits following the area code) would be parsed into a list of possible phone numbers belonging to the target, with number prefixes ranging from 200-999.

The exact phone number would then be confirmed by submitting phone numbers from the compiled list to the ‘Forgot password’ page on Facebook, and looking for when the full name of the target is returned, or when distinctive characteristics—such as an unusual e-mail address domain are found to match with the originally provided e-mail address.

The websites mentioned in this report play an pivotal part in allowing for extrapolation of obfuscated phone numbers, however, it should be noted that the sites mentioned are only two from a list of several other popular websites which pave way for the same end result.

For example, Yahoo! gives away the first and last two digits of the phone number when attempting to reset an account password.

The general public can combat part of the issue by using varying phone numbers when signing up for different online services, and by refraining from providing personal phone numbers to websites that reveal partial phone number information on their password reset pages.

Update: April 11, 2018 – An earlier version of this article appears in the Spring 2018 issue (Volume 35-1) of 2600 Magazine.